For centuries, the Indian monsoon has been more than just a weather cycle, it has been a cultural and civilisational anchor. In Meghaduta, Kalidasa immortalised the monsoon as a celestial messenger, painting landscapes with longing and renewal. In Tagore’s New Rain (Nababarsha), it breathes life into parched lands, heralding transformation and hope. This seasonal rhythm once nourished our agriculture, inspired our poetry, and invigorated our landscapes.

But today, in the heart of a rapidly modernising India, the monsoon has become an uncomfortable mirror, reflecting not romance, but ruin. It no longer just brings water; it reveals the rot within our infrastructure. From airport terminals collapsing under heavy rains in Delhi to breached tunnels, such as the Srisailam Left Bank Canal in Telangana, and sinking highways in Jammu and Meghalaya, each monsoon now lays bare not just cracks in concrete but also deep fissures in planning, oversight, and accountability.

This piece does not target any one government, corporation, or entity. It is an inquiry into a troubling question: why has modern India, with its access to advanced technology, greater budgets, and ambitious infrastructure policies, failed to build with the resilience and foresight of its ancestors?

Consider what we have inherited. The Harappan civilisation engineered drainage systems that are still admired for their efficiency. The Chola dynasty built temple complexes that endure cyclones and monsoons. The Mughal era constructed aqueducts and bridges with remarkable longevity. These were not accidents of genius; they were the product of meticulous engineering, sustainable materials, and an understanding of climate and geography. They were built with a purpose, not just for optics.

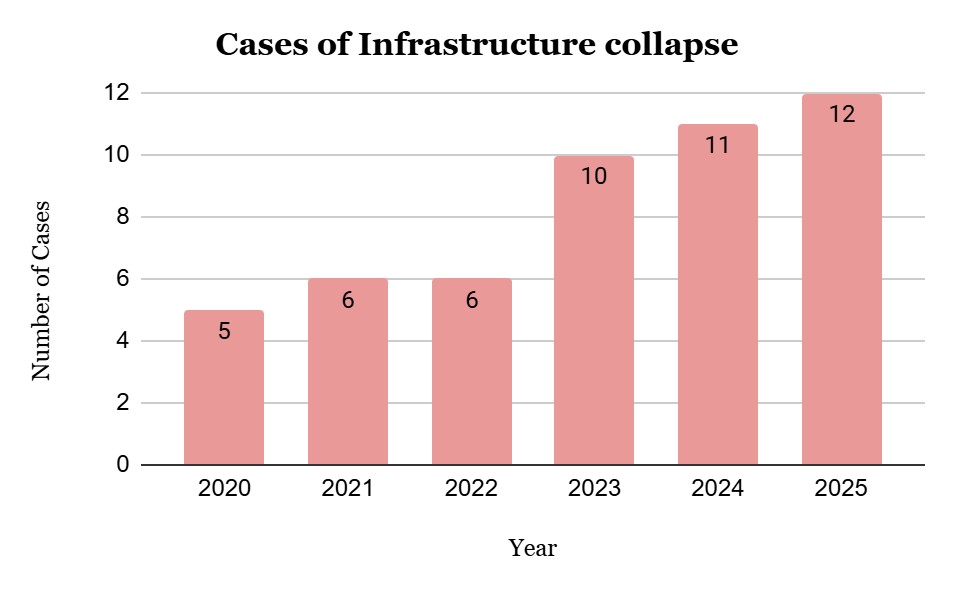

Now, contrast this legacy with the track record of recent years. Based on media-documented cases from the last six years, focusing exclusively on newly constructed infrastructure such as roads, bridges, dams, and tunnels, there has been a clear and worrying rise in infrastructure collapses. As illustrated in the chart, the number of cases increased from 5 in 2020 to 12 by 2025, more than doubling in just five years. The years 2023 to 2025 alone witnessed 33 failures, indicating a steep upward trajectory.

Graph 1: CRF Analysis by Shivani Patel

The Lingasamudram Bridge in Andhra Pradesh collapsed merely a year after its completion in 2020. The Parbati II dam in Himachal Pradesh gave way in 2021. The Ghodasan Bridge near Champaran, Bihar, collapsed in 2024. In addition, highways in Meghalaya, Jhunjhunu, and Haryana disintegrated during the seasonal rains, while tunnels under construction, such as the Kohima bypass and the Telangana canal tunnel, caved in mid-project. These are not engineering errors; they are symptoms of a larger systemic failure in governance, regulation, and public engagement.

So, what explains this deterioration?

The rising frequency of infrastructure failures in India is not the result of a single flaw but a dangerous convergence of systemic issues. At the heart of this crisis lie three reinforcing pathologies, First, Ignored Expertise, in several high-risk infrastructure projects, expert advice and geotechnical assessments have been either ignored or entirely absent. The Silkyara Bend–Barkot Tunnel in Uttarakhand and the Cafeteria Morh tunnel along the Jammu–Srinagar NH-44 were both undertaken in seismically fragile terrain within the Pir Panjal range yet treated as routine hill-road expansions. The result was catastrophic failure. Similarly, the Srisailam Left Bank Canal (SLBC) tunnel collapse in 2025 occurred despite a separate geological survey in 2022 flagging safety concerns. A glaring example of poor design is the Bhopal 90-degree flyover, constructed at a cost of ₹18 crore, which is now set to be demolished due to the absurdity of its 90-degree turn making it both a planning and engineering embarrassment.

Second, Weak Regulation, Legal frameworks exist but are poorly enforced or structurally inadequate. The Dam Safety Act of 2021, though a step forward, suffers from weak implementation. Tunnel construction continues to be governed by inconsistent, state-specific rules, lacking a unified national framework for risk assessments in monsoon-prone or seismic zones.On-ground quality checks are either cosmetic or manipulated. Take the Mumtapura Bridge collapse in Gujarat (2021), where collected samples of cement and sand from ready-mix concrete plants failed to meet prescribed standards. In Baghwali-Jahaj, villagers flagged the use of substandard materials and requested culverts to mitigate flood risk—but their concerns were ignored. There is also no emergency protocol in place for under-construction projects, and no system exists to assess the ecological or load-bearing limits of bridges in sensitive areas like the Himalayas, setting them up for structural overload.

The final and perhaps most insidious factor is institutional apathy. Across multiple levels of government, there is no clearly assigned responsibility. Central, state, and local agencies operate in silos, often passing the blame in times of crisis. Urban development authorities routinely skip inspections. Contracts are rushed to meet political timelines such as those hastily inaugurated before the Election Commission’s Model Code of Conduct despite being incomplete or unsafe. Contractors are rarely blacklisted. Bureaucrats are shuffled to other postings. Judicial redress comes only after public outrage or loss of life.

And yet, amid all this dysfunction, one truth is harder to confront, i.e. citizens, too, have failed to play their role. Infrastructure is built from public money. But the public remains largely silent. According to the Central Information Commission’s 2023 report, less than 5% of RTI applications filed relate to infrastructure. Public interest Litigations in this area are even rarer. This is not just apathy, it is complicity. Democracy is a two-way street, and the social contract demands more than votes. It requires sustained vigilance.

Have we become so used to low standards that we no longer expect, let alone demand, better?

The cost of this collective failure is staggering. Between 2021 and 2025, 50 major infrastructure failures were recorded, with estimated damages exceeding ₹5,000 crore. In some cases, the government has floated a tender for demolishing the structure due to concerns about its poor quality and safety. Roads with potholes, crumbling edges, and inadequate drainage are not just an inconvenience; they are a danger. In 2022 alone, 4,446 road accidents were caused by potholes, resulting in 1,856 fatalities and 3,734 injuries. That same year, 9,221 people died in accidents related to ongoing road construction.

This does not even account for the incalculable loss of life, productivity, and opportunity. When the infrastructure collapsed it isnt just a tragic accident; it disrupted logistics, and choked the economy. In rural areas and small towns, infrastructure is not about convenience; it is about survival. Roads and bridges are the only links to schools, hospitals, and markets. In parts of Assam, the collapse of key bridges has left entire communities cut off from the mainland. Sometimes, the failures aren’t just domestic disruptions; they are strategic risks. The collapse of a Bailey bridge in Arunachal Pradesh cut off vital connectivity to India’s eastern frontier with China. In such geopolitically sensitive regions, infrastructure isn’t merely a development agenda; it is a national security imperative.

Reform is no longer a choice; it is a necessity. What India needs is a systemic overhaul that brings together political will, engineering expertise, environmental foresight, and institutional accountability. Policy reform must begin with empowering regulatory institutions both legally and financially to enforce compliance. The Dam Safety Authority, for instance, must be operationalised with independent powers and binding oversight capacity, not just advisory roles. Project Management Units (PMUs) should be embedded within all infrastructure agencies to ensure real-time monitoring, third-party auditing, and transparent reporting. All major tenders should be accompanied by publicly disclosed risk assessments, especially for geologically fragile or climate-sensitive zones. Local governments must be entrusted with on-ground inspection authority, equipped with engineering staff and digital tools to monitor quality benchmarks. Simultaneously, a National Infrastructure Safety Dashboard should be established to flag delays, quality lapses, and accountability gaps across ongoing public works.

But perhaps most importantly, we must learn from our successes, not just failures. The Atal Tunnel, cutting through the Rohtang Pass at over 10,000 feet, remains operational through some of India’s harshest winters because the project was guided by meticulous planning, geotechnical surveys, and a no-compromise approach to safety. The Chenab Bridge, the world’s highest railway bridge, survived Himalayan winds and seismic shocks due to precision engineering and risk mapping at every phase. These projects stand as proof that India can build world-class infrastructure when political resolve, engineering discipline, and institutional integrity converge.

What makes these projects different is not just the ambition it is the process. These weren’t rushed for electoral gains. They weren’t undermined by poor quality material. They didn’t ignore the terrain or silence the engineers. They were built with intent, patience, and accountability. It is time to make this the norm, not the exception. Projects are not failing because we lack the knowledge to build better they are failing because we have normalized cutting corners. Projects don’t go wrong—they start wrong. The true failure lies not at the site of disaster, but at the moment we normalize compromise. And if we, as citizens, choose silence over scrutiny, then we are not just bystanders to failure, we are co-authors of it.

Himani Agrawal is a Research Analyst at the Centre for Economy and Trade at Chintan Research Foundation. She is Post graduate in Public Policy and Management and has a bachelor’s in economics. Her research interests span infrastructure development, public finance, geo-economics, and welfare economics.

(Cover Photo: Most roads in India are always waterlogged during the monsoon due to improper drainage systems and poor civic amenities and infrastructure. Photo Credit: Nitin Joshi)

CICCollapsed SystemsExpertisegovernment of indiaGraph 1: CRF Analysis by Shivani PatelHighwaysIndiaInfrastructureMonsoonPoliciesRoads