As India enters a period when a great economic expansion is most possible, it would be unwise for it to get involved in an expensive and debilitating international rivalry

Tibet is not only India’s largest geographical neighbour but also its most significant in terms of the environmental impact. Many major Indian rivers like the Brahmaputra, Indus and Sutlej originate in Tibet. Though we have been brought up to believe that the Himalaya are an impenetrable barrier, they are in fact quite porous and the ethno-cultural traits of the people who inhabit the crest of India amply reflect the influence of Tibet in Indian culture. This to and fro movement of people continues even today despite the deployment of the world’s two largest standing armies in a bid to define borders. India’s influence on Tibet too has not been insignificant.

Despite a political identity that has historically been entwined with China’s, Tibet has traditionally looked towards India for economic and spiritual sustenance. Tibet has also had a long history of struggle with China and this Dalai Lama is not the first one to seek refuge in India. The British had an active policy to create a buffer against China in the form of an independent Tibet. Not only that, the British also sought to open Tibet to the world and to its influence. When the Tibetans proved recalcitrant the British sent in a military expedition led by Col. Francis Younghusband to do just this. The Chinese Amban in Lhasa watched the Younghusband expedition’s exertions in Tibet passively and one immediate consequence of this was an assertion of Tibet’s independence.

Almost immediately after their civil war triumph in 1949, the Chinese Communists reasserted control over Tibet, which had by then enjoyed over four decades of relative independence. Since then India has tried to head off the Tibet problem by accepting its annexation by the People’s Republic of China. In these 56 years, the Chinese Communists initially tried to solve the Tibet problem by attempting to wipe out Tibetan nationalism and Buddhism with Mao’s Communism. It didn’t succeed. This policy has now been replaced by creeping “Hanization” and massive doses of economic development. These too have worked only partially for the Chinese, but they seemed to do better with this than with the Maoist iron hand. Though Tibet is now relatively passive, it still remains a dry tinderbox and the Chinese dread the likelihood of any spark that may set off a fire.

Though we have been brought up to believe that the Himalaya are an impenetrable barrier, they are in fact quite porous and the ethno-cultural traits of the people who inhabit the crest of India amply reflect the influence of Tibet in Indian culture.

For India too the policy has worked partially. Nearly 150,000 Tibetan refugees now live in India, and India has willy-nilly become the fulcrum of a worldwide struggle by the Tibetans to regain their nation. In short the Tibet issue, though dormant now, is still very much alive and whether India likes it or not, it is being played out in its front yard.

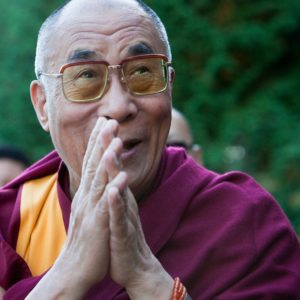

The stature of the Dalai Lama

The stature of the Dalai Lama

Central to this sustained struggle has been the ever-increasing international stature of the Dalai Lama who has become the symbol of many ideals and images. The mix of new age spiritualism, ethics, ecological values and politics has won for the Dalai Lama many influential and wealthy western adherents to Tibetan Buddhism and supporters of Tibet’s cause. McLeodganj today is a magnet that draws large numbers of young westerners seeking a new meaning to and purpose in life.

Tibetans believe the Dalai Lama to be a living God. But he is also human and must die like all humans. He is now in his 81st year and time is certainly not on his side. As long as he is alive he keeps the embers of Tibetan nationalism from conflagrating with the blanket of the new age Buddhism that he has woven.

True, the Dalai Lama has become many things to many people but what should be relevant to us is that he has emerged as a man of great stature and influence. Presidents and Prime Ministers now vie to receive him and the pictures that get transmitted the world over electronically remind the world that there is still a Tibetan nation yearning to be free and peacefully struggling for it. This is a powerful image.

Stalin did not live to see his wry question about the number of divisions with the Pope answered. But one must wonder what he would have had to say if he had witnessed the Polish priest who became the Pope catalysing the collapse of the Communist regime in Poland, which in turn unravelled the Warsaw Pact and Soviet hegemony over Eastern Europe. The Chinese have a better sense of history and hence rightly worry about the broad wake the peripatetic Dalai Lama leaves behind as he reiterates his message all over the world. India too must worry about this.

Tibetans believe the Dalai Lama to be a living God. But he is also human and must die like all humans. He is now in his 81st year and time is certainly not on his side. As long as he is alive he keeps the embers of Tibetan nationalism from conflagrating with the blanket of the new age Buddhism that he has woven. When this Dalai Lama is gone, the embers might just combust.

Post-Dalai Lama scenario

We can be certain that it is the present Dalai Lama’s stature that keeps the lid on Tibetan militancy. After him, the political power of the next Dalai Lama will almost certainly be challenged. Many of the younger Tibetans in exile will not accept the legitimacy and leadership of another incarnation. The incarnation will, in any case, take many years to grow into mature adulthood and till then some manner of bureaucratic regency will actually be in charge. This regency may not have the moral and spiritual stature of the present Dalai Lama. That will have to be earned and only time can tell if the next incarnation chosen by the regency will fit the bill.

The chosen leadership of the exiles will not go unchallenged. The Chinese will almost certainly try to foist their own incarnation and will try to legitimise it with all the power available to them. It is unlikely that they will succeed, but it will certainly obfuscate the situation and preclude any future compromise on the issue of the spiritual leadership of the Tibetan Buddhists.

While the spiritual leadership may be contested, it is almost inevitable that a new generation of Tibetan exiles will stake a claim for the temporal leadership of the Tibetan nationalist movement. If this is contested by the regency around the India-based incarnation, then we will almost certainly see a competition for the hearts and minds of young Tibetans and this will inevitably lead to more assertive postures as the factions jockey for power. Such internal struggles often result in greater militancy.

On the other hand, we may see a duality of leadership emerging among the Tibetan exiles, a spiritual leadership that tends to the soul and a militant leadership that leads the struggle for attainment of political goals. It is due to the Dalai Lama’s foresight and sagacity that the contours of such a dual leadership are emerging with the second tallest Buddhist ecclesiastical figure, Ugen Thinley, the Karmapa, and the just re-elected Sikyong (Prime Minister) of the government-in-exile, Lobsang Sangay. Both now enjoy much stature among émigré Tibetan groups and with vast sections of Tibetans in Tibet.

The splintering of the exile leadership into two or even more factions would be a desirable objective for the Chinese. From the Indian perspective the rise of an alternative religious leader in the interim would well prevent the splintering of the Tibetan Buddhist movement. The young Karmapa might well provide this.

They also darkly hint from time to time that the Dalai Lama is the sharp end of a deep wedge sought to be driven into China to disrupt its historical unity.

Some possible consequences for India

This will not be without consequences for India. People who have closer ethno-linguistic links to Tibet than to the plains populate the entire Himalayan region from Ladakh to Arunachal Pradesh. Geographically, much of Ladakh is an extension of the Tibetan Changthang and the main language spoken is a Tibetan dialect. The Tawang tract, at the other end, was, till it was annexed by India in the early 1950s, under the temporal control of the Dalai Lama in Lhasa. The Bhotias of Sikkim are also a Tibetan race speaking a Tibetan dialect. The term Tibet derives from Tho Bhot, the original denotation for Tibetans. It is not difficult to see the relationship between Tho Bhot and Bhotia.

The Dalai Lama has so far shown great restraint by not overtly interfering with the functioning of the numerous monasteries, but a future religious leadership might not be so restrained, particularly when there is so much easy western money involved. In a nation where sub-national separatist movements are constantly erupting, the possibility of this being stoked in the Himalayan region should not be excluded.

We must not forget that the border dispute with China is in reality a border dispute with Tibet. It is another matter that if Tibet was independent, and hence weak, it would have been unable to assert its claims in the manner the Chinese did. The Chinese claim to the Tawang tract is largely based on a claim made by the present Dalai Lama in the late 1940s when he wrote a letter to the government of newly independent India laying formal claim to it.

The present situation

The Chinese are very clear about what they think about the Dalai Lama. They mince no words and describe him variously as a duplicitous, treacherous and fraudulent troublemaker who is more of a political leader and less of a religious preceptor. They also darkly hint from time to time that the Dalai Lama is the sharp end of a deep wedge sought to be driven into China to disrupt its historical unity. They also unequivocally dismiss all claims of an independent Tibetan existence for over a thousand years at least. They describe the Dalai Lama espousing the yearnings of a suppressed Tibetan people as the yearnings of a power-hungry feudal wishing to re-establish a primitive and medieval system once again over a long tyrannised people. The Chinese believe that the majority of the Tibetan people are happy and thriving after their liberation by the Communist Party. They may well be right, but history tells us that it is always a determined minority that empires have to worry about.

The new post-Communist China thus reserves the highest premium for “internal harmony” while it is embarked on the rapid transformation of its economy within the window of opportunity its current demographics offers. Three decades from now, China will be an aging nation and hence it feels that it must make the best of the present opportunity. This is the dominant mood among China’s leaders and they would be extremely loathe to let the ambitions of a relatively small number of Tibetans distract them from the goals they have set for China. China can contemplate two or more systems within one nation, as is now the case with Hong Kong and on offer to Taiwan. This is essentially a common economic system with a fairly generous allocation of administrative power, as we see in the case of Hong Kong. What system can the Chinese offer the Tibetans? The Dalai Lama is increasingly speaking about a Buddhist way of life in Tibet within China. How can China agree to this when it essentially undermines the political authority of the centre?

BuddhismChinaConflictDalia LlamaDoklamIndiaIndo-China RelationsTibet