This is the second part of Amit Sengupta’s musings about journeying through a nightmare based on the experiences of Czech writer and leader, Vaclav Havel, Franz Kafka or Arana Neumann’s who reminisces about her peripatetic father who leaves fascist Germany to settle in Latin America, a haven for all revolutionaries on the run. Is there an escape from the unfolding nightmare?

Editor

“I miss you deeply, unfathomably, senselessly, terribly.”

― Franz Kafka, Letters to Milena

“The fact that no one knows where I am is my only happiness. If only I could prolong this forever! It would be far more just than death. I am empty and futile in every corner of my being, even in my unhappiness.”

– Franz Kafka, Letters to Felice

I had a book, long, vertical, beautiful book in black and white, stolen from my room at Sutlej Hostel, JNU, during those heady days, among other stolen books or books unreturned, like Franz Kafka’s letters to Milena and Felice. Kafka’s obsessive, possessive, liberating, lovesick, infatuated, eclectic, never-liberating letters to his unrequited beloveds! The book was about the streets of Prague, where Kafka, presumably walked. A beautiful book about streets in black and white.

Vaclav Havel, the great writer and rebel against the totalitarian ‘communist’ regime in Czechoslovakia, who later became president after the Prague Spring (where is he now?), once wrote that when he sleeps in the night, he thinks that the next morning he might wake up in a dark prison, perhaps a one-celled room. As in Portland, America, where US President Donald Trump is using mercenary Feds to smother protestors like they did in Jamia and JNU, or as in Delhi and in rest of India where young students are in jail on cooked up charges under a fascist regime. Havel’s is not an impossible dream.

Or a nightmare.

So what did Karl Marx say? History repeats itself as what? A farce, a tragedy, or, as a nightmare? A nightmare in a pandemic? So is there hope after a badly written and scripted nightmare that made no historical or rational sense in a democracy? Or is it a bad dream in bad faith?

In Prague before the fascists entered those days, there were dreams. Mila and Hans were in love. And so was his tall brother Lotar with Zdenka. Their father Otto with a loving mother Ella ran a small paint factory called Montana.

Remember Junaid? Or Pehlu Khan, or Akhlaq of Dadri with meat in his fridge, lynched to death as a predictable soap opera, or all those mob-lynched in Jharkhand and elsewhere as a meticulously planned project

In the autumn of 1941, after the fascists were well-entrenched in Prague, and the Holocaust was on in its full cannibalistic and carnivorous bloom for the entire world to see, Hans was asked to deliver a letter to another nearby factory. “He walked in and met the owners’ daughter, Mila, who was working as a receptionist. Hans was a timid 19 year old. … She had Rilke’s ‘Book of Hours’ open on her desk. Hans handed her the Cermak envelop and, noticing the book as well as the girl, managed to hold her gaze and muster a line by the poet: ‘Nearby is the country they call life’…Mila explained to her son many decades later that it was precisely at the moment she fell in love with Hans.

So whatever happened to Mila and Hans and their secretive, epical love, in the time of fascism? Or, was it a chronicle of a tragedy foretold?

The great, passionate love of Lotar and Zdenka, celebrated for all friends and relatives in their engagement, what happened to that love and that passion. Her family warned her, don’t do it, he is a Jew. They still did it, and went through it for months? What happened to their love?

There were 34 members of the Neumann Haas family living happily in Czechoslovakia in 1939, when Adolf Hitler attacked Poland, started his genocidal world conquest, and the Second World War started. Three of them were “either gentile or ‘mixed’ and too young to be deported. Hans and his brother Lotar escaped through a mix of incredible good luck, good strategy and good help from friends and unknown sources. All of them, 29 of them, between 8 to 60, deported to the concentration camps in their own country, and to Germany, Poland and Latvia – whatever happened to them?

Four came back.

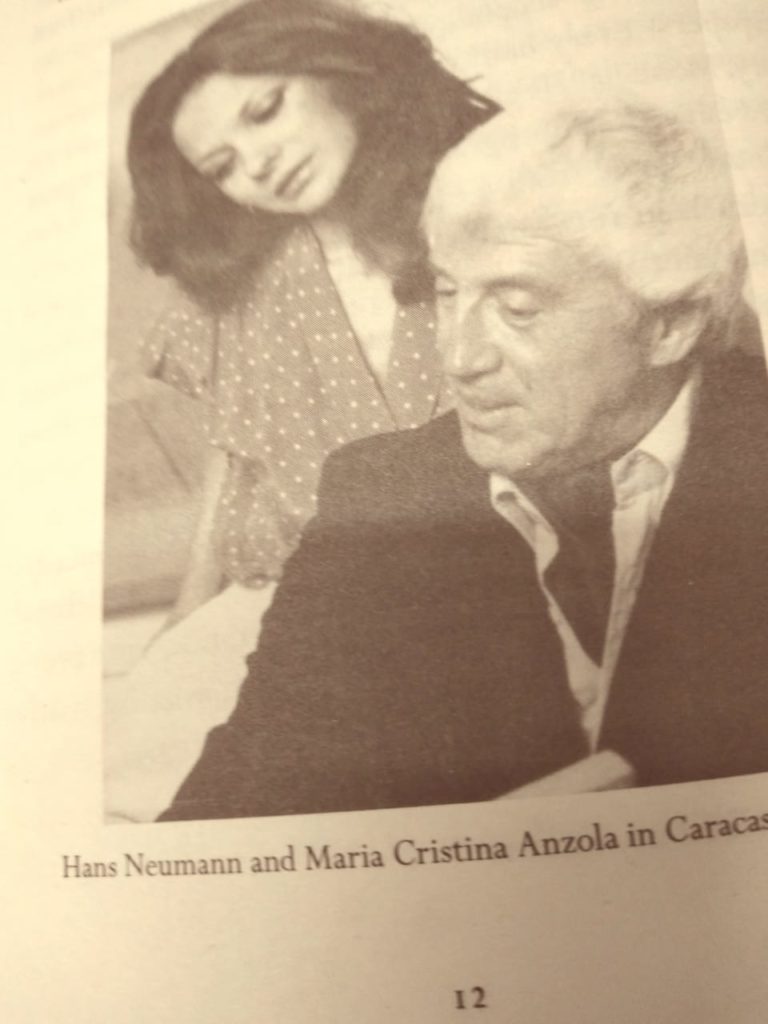

Ariana Neumann is the daughter of Hans Neumann, son of Otto and Ella and brother of Lotar. She is not a social scientist or historian or journalist. She was just a daughter happily married, totally unaware of her past. Or, her father’s past.

She was part of a family, which had ‘escaped’ in the 1940s to guess where? Venezuela. Many from Central Europe had been given shelter in that country at that time. Indeed, several communist rebels escaped to Latin America during those times including from Franco’s fascist regime in Spain, after a million sacrifices by the rebels, in a war they did not completely lose, really. They lost finally, yes.

Ariana’s journey with her father’s memory, who never told her a word about his past, and who was opposed to Hugo Chavez, does not have any tragic mappings foretold, not a dramatic or melodramatic breaking heart nuance.

Her father was surely not a communist. Instead, he became a mighty capitalist in Caracas, controlling huge empires, possessing the finest and most expensive art works as an art connoisseur, became an educationist and philanthropist, and lived a life of the super rich with ‘taste and refinement’ in a palatial house, where a nude painting would astound his rich friends’ wives and mothers. Don’t look at that painting a mother would tell her daughter and thereby they would never visit the house.

A disciplined man, he would have his Campari after his work in the night on the balcony with a straw, which would leave an imprint on the fine fabric of the table that his little daughter would remember all her life like his grandfather’s beautiful watch. The watch is only a metaphor for time. He would read the papers when dawn would break, and then his little daughter, Ariana, would enter his room, and he would give her the crossword puzzles. In the evening his beautiful wife, not Mila, but Maria, whose wealthy parents came to Venezuela in the early 17th century, would go for a party occasionally, she resplendent in her flowing dresses.

Until she discovered his name in a museum or a memory gallery of those who were killed in the concentration camps. There was a question mark in front of his name. Silence. Did he die, Hans Neumann, like his entire family in the concentration camps? Or did he escape like Lotar from the country? Who was he and what happened to him? Was he taken to the ‘detention camp’ to Terizin, and beyond and why? Why not?

Termites and vermin, Jews and Muslims, Dalits and Adivasis, students, dissenters and rebels, intellectuals and academics who dare to defy, ordinary people who subvert and did not toe the line: somehow, it all comes back in this recent book by Ariana Neumann – When Time Stopped; a Memoir of My Father’s War and What Remains (Simon and Schuster, UK).

Simply said, the book is about a daughter who has lived her life in Venezuela, searching for her roots in Prague and her own original homeland, before and after Vaclav Havel and the Prague Spring, and rediscovering boxes after boxes, discarded, lost, forgotten, from distant geographies and lost cousins, often wet and immaterialized and etherized, often uncontrollably not decipherable like lovesick love letters written in passion and hurry, most often faded memories of memories which she just could not understand and situate in the history of the times when she was not born.

Like the hounding which began soon after the fascists came inside Prague and elsewhere in the country. You can’t talk to the Jews. They can’t marry or have friends with non Jews. Sex with a non-Jews was also a crime. They could not swim in ponds or lakes or walk on the streets where everyone walked. Not even in the forests. They had no personal property or fundamental rights. They will never marry a non-Jew. They will work as bonded or slave labour. They can’t travel on the same trains, or live in the same homes. They will have no neighbours or social life or schools or friends or barbers or nieces and nephews and grandchildren and uncles and aunties, no school for them would be allowed. They cannot sing or pray or talk loudly. They are second class citizens, period. They don’t exist as slave labour, or potential name tags to be transported to detention or concentration camps.

There were many letters. And pictures. Happy pictures. Pictures of love and sharing. Family memories. Many sad letters from the detention centres. Some asking for food, as starvation stalked them. Or death. Or escape.

So what did Karl Marx say? History repeats itself as what? A farce, a tragedy, or, as a nightmare? A nightmare in a pandemic? So is there hope after a badly written and scripted that made no historical or rational sense in a democracy? Or is it a bad dream in bad faith?

No escape. Lotar wrote about the ‘stars’, marking Jews on their foreheads, to his uncle in the US:

‘Then came a further landmark in our lives; ignominious labeling with a yellow star. This was such a ghastly humiliation that many took their own lives rather than move among others differentiated and disgraced in this way. It gave every black guard an opportunity to spit, slap or kick you, And it was as if the German SS men had found a new sport, that of throwing the Jew out of the moving tram. They would watch and laugh and wait to see whether the poor wretch would break a rib or an arm or a leg. The worse the break the louder the laugh. It was a prelude to what would come a month later in October 1941, the transports.”

Somehow it reminds me of the train journey of Junaid, in the outskirts of Delhi on the festive day of Id, after religious fascists came to power in Delhi and unleashed a wave of hate politics and mob-lynching. Remember Junaid? Or Pehlu Khan, or Akhlaq of Dadri with meat in his fridge, lynched to death as a predictable soap opera, or all those mob-lynched in Jharkhand and elsewhere as a meticulously planned project, almost as a public spectacle with a nebulous mastermind or is it the ideology- calling the shots and the entire administration and cops backing them. And after the deed, killers, sometimes, garlanded by a Union minister?

The transports. Across the beautiful European landscape. In ghettoized, holed up, dark, breathless, stinking, dehumanized, brutalized, railway compartments. Rotting bodies amidst rotting shit, starving and emaciated, taken to unknown destinations. Through the lovely tracks of sublime beauty outside. While Europe watched and the world watched.

To the gas chambers, the death and labour camps, the Holocaust. Onwards the trains came one after another!

Ariana’s journey with her father’s memory, who never told her a word about his past, and who was opposed to Hugo Chavez, does not have any tragic mappings foretold, not a dramatic or melodramatic breaking heart nuance. The nuance is in the telling, which is a deeply personal history, also collective history, of her times. Our times. Indeed, she never utters a word against Chavez or the communists. No one utters a word against Chavez in this book. Only, yes, she does mention, so obliquely, that her father, a capitalist, was against Chavez.

This book is not about Chavez, the great man. Nor is it about the communists in Venezuela,or the dictatorship of the Stalinists and Soviet communists in Prague which led to the Prague Spring, as it did in Poland under the leadership of Lech Walesa, who led Solidarity, the workers party of the port workers of the Shipyard of Gdansk. It is also not about why people in Poland or Prague hated both the Nazis and the communists. It is about her roots. And how the Nazis snuffed out all the happy pictures of her beautiful family.

Compare it to the hard reporter’s meticulous notebook documented with as much detachment as possible on a subject loaded with infinite injustice and relentless remorse. Hanna Arendt’s ‘Eichmann in Jerusalem’ documented in the issue of The New Yorker, February 16, 1963, under the title. ‘Reporter at Large,’ is a classic testimony. Something we must do too in India one day, though the Gujarat genocide, 2002, and the 1984 State-sponsored killings of Sikhs in Delhi and elsewhere, and the Bombay pogram in the winter of 1992-93, among others, including the massacres of Muslims in Maliana in Meerut, UP in 1984, remains entrenched as memory and nightmare. With no or little justice.

Writes Arendt:

“…Eichmann’s own attitude, it appeared, was different. First of all, the indictment for murder was wrong: ‘But I had nothing to do with the killing of the Jews. I never killed a Jew, or, for that matter, I never killed a non-Jew—I never killed any human being. I never gave an order to kill a Jew nor an order to kill a non-Jew; I just did not do it.’ Or, as he was later to qualify this statement, ‘It so happened . . . that I had not once to do it’—for he said explicitly that he would have killed his own father if he had received an order to that effect…”

That Eichmann presided over the killings of millions, did not affect him to the least. He suffered no guilt at all. That was an enigma and that is never an enigma. Wrote Walter Benjamin, the great thinker of ‘Illuminations’: There is no document of civilization which is not at the same time a document of barbarism.”

It is like those pictures of dead Jews scattered on the streets, curled up, rotting, without dignity or an end. Just lying there as they should be lying there as we pass by. And then the Nazis clicking pictures of a lovely outing.

It’s like a Nazi officer of a concentration camp, having gassed to death thousands of Jews, and of course mentoring the sexual slavery of Jewish women in their own affluent residential camps where they would party all night, coming home for a holiday with his family. So he would go for a picnic with his loving devoted wife and kids, and drink his wine and sing his German songs full of nostalgia of pastoral nostalgia , and that is what it would be.

Life is always elsewhere, as Milan Kundera said.

concentration campsfascistsHitlerhugo chavezrevolutionarythoughtworld war 2