By Monira Ahsan, Asian Institute of Technology in Bangkok

Despair and hopelessness envelop the 13 square kilometre space in Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh which makes up the world’s largest refugee camps housing nearly 1.2 million Rohingya refugees, 51 percent women and 49 percent men, spread across 33 camps. Conditions are poor with a lack of the most basic of human needs such as clean water, sanitation, proper food and shelter and medical support. There are also major issues with safety and security.

But notable is the depression that is prevalent throughout the Bazar mirroring the pessimism with which the refugees view their situation. “We do not see any hope in our life,” said one Rohingya while another added, “ We are agitated, angry, hopeless, and fearful.”

Various factors, including congested shelters, reduced food aid and nutrition, degrading water, sanitation and hygiene facilities, and environmental degradation contribute to the poor health of these Rohingya refugees.

There is also a gap in investigating the gendered dimensions of health among Rohingya refugees.

Existing studies focus on various aspects of physical and mental health with a limited focus on sexual and reproductive health.

Studies show that the vast majority, 72 percent of the studied Rohingya women, have experienced various forms of gender-based violence. More than half of the studied Rohingya women (56.6 percent) had experienced unwanted sexual intercourse with their husbands, resulting in unwanted pregnancies and unsafe abortions.

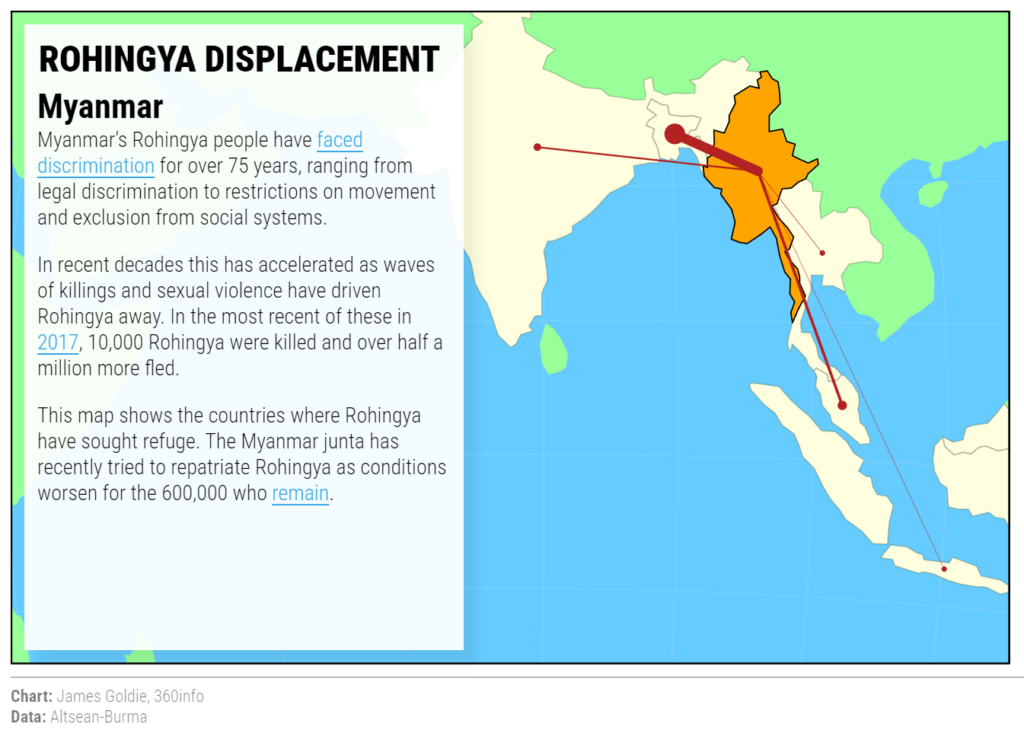

Rohingya refugees survive in countries throughout Asia-Pacific.

Apart from this, hundreds of thousands of Rohingya people in Cox’s Bazar have been suffering from severe skin diseases which led the World Health Organization (WHO) to carry out a large-scale Ivermectin-based mass drug administration (MDA) campaign. A WHO survey in May 2023 revealed 39 percent of the camps’ population suffered from scabies. NGO Doctors Without Borders made similar findings, backing the WHO report, which also suggested the prevalence of scabies was as high as 70 percent in some camps. Congested living conditions and poor water and sanitation facilities are the root causes. A lack of functioning latrines exacerbates the poor health conditions. The situation is worse for women as they are mostly confined to the shelter with restricted access to the already poor water and sanitation facilities. Majhi, the leader of Camp Six said, “Our women stay at the shelter most of the time, and also cannot use the toilets as and when needed that are away from the shelter and in public spaces. This causes various health problems.” Drawing on findings from a recent scoping review, Rohingya refugees also suffer from various mental health symptoms. The prevalence of depression ranged from 12 percent to as high as 89 percent among the 33 camps in Cox’s Bazar. Similarly, post-traumatic stress disorder ranged from 3.7 percent to 61.2 percent. Anxiety prevalence was recorded from 9 percent to 70 percent. Other psychological symptoms included persistent complex bereavement disorder (7 percent), feeling bad (50.4 percent), feeling afraid (14 percent) and feeling angry (9 percent). Anxiety and depression were more prevalent among female refugees compared to men, who suffered more from post-traumatic stress. However, both females and males highlighted their deteriorating mental health conditions in statements like this one by a female refugee in Camp 3: “We do not see any hope in our life. There is no possibility of integration or repatriation. Being trapped in this camp life makes us depressed.” A male refugee in Camp 1E said: “In the early years of our arrival, we were quite optimistic that we would have a life choice. But as time passes, we become disillusioned. Our people have started embarking on the risky journey to a better life, whereas many others are getting involved in drug trafficking and drug addiction. “Some of us must spend sleepless nights maintaining security in the camps. Such a situation makes us agitated, angry, hopeless, depressed, and fearful for our existence.” UN agencies and NGOs have only limited mental health initiatives in the camps. Sexual and reproductive health is also a major challenge for Rohingya women and girls. An absence of clear abortion policies, a lack of knowledge and understanding of abortion laws and policies, coupled with a lack of privacy in health centres, limited cultural safety, personal belief, and differences in knowledge of menstrual regulation among healthcare providers reduce the access and utilisation of comprehensive abortion care among Rohingya women and girls. As one sexual and reproductive health practitioner in one clinic at Lambashia Camp explained: “The Rohingya women and girls are concerned if anyone has seen them visiting the health centres and receiving sexual and reproductive health services. Moreover, those who have received these services tend not to visit health centres for follow-up treatment. “Our health centre employs community health workers and a few of these male and female workers are from the Rohingya community. However, the very infrastructure of the health centres lacks privacy. “Besides, there is a strong religious belief and sentiment among Rohingya people not to opt for family planning. Besides, women and young girls suffer from inconsistent supply of menstrual hygiene kits and poor hygiene facilities causing various sexual and reproductive health problems.” Dwindling humanitarian aid, coupled with social norms and beliefs, has resulted in poor health among Rohingya refugees, particularly for women, children, people with disabilities and gender-diverse populations. The engagement of national, regional and international actors to impact policies, practices and research can be considered to solve this protracted humanitarian crisis of Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh.

Dr Monira Ahsan is a post-doctoral researcher at the Centre on Gender and Forced Displacement (CGFD) in the Department of Development and Sustainability at the Asian Institute of Technology.

This article is part of a Special Report on the Rohingya refugees produced in collaboration with the Calcutta Research Group and the Asian Broadcasting Union.

Originally published under Creative Commons by 360info™.