I first met Dharmendra in May 1992. I had just been posted to Bombay, and a friend-cum-batchmate, whose family was related to Dharmendra, took me one Sunday to his Juhu bungalow to introduce me. I was a huge fan and had lived on a diet of Dharmendra movies, having seen almost his entire repertoire – from his inaugural Dil Bhi Tera Hum Bhi Tere (1960); through the 60s with Shola Aur Shabnam (1961), Bandini (1963), Haqeeqat (1964) (being a fauji child, the film had resonated with me deeply), Mamta and Anupama (both 1966), Satyakam (1969); the films of the 70s such as Naya Zamana (1971), Chupke Chupke (1974), Sholay (1975), Kinara (1977); and the 80s with Razia Sultan (1983) and Ghulami (1985). Throughout his career until then, Dharmendra had his foot firmly on the pedal, and by the time I arrived in Bombay in the early 90s, nothing had changed.

I hadn’t seen a handsomer man than him, a more macho man than him, a funnier man, a more sensitive man, a more modest and down-to-earth man, or a more devoted family man.

My friend knew about my affection for him and his formidable body of work. So he took me to meet him.

Seldom does a celebrity, when met in person, live up to the lofty expectations of the pilgrim. Feet of clay often reveal themselves. But Dharmendra didn’t disappoint.

The massive drawing room had several seating sections. Dharmendra sat in the central one with producer Madan Mohla. His film Humlaa had been released two days earlier, and Mohla was on the phone with distributors and exhibitors across the country seeking updates. Dharmendra motioned for us to sit and indicated he would join us shortly. The loud, brusque, curse-filled conversations of Mohla elicited a smile from Dharmendra – the film’s hero. (Madan Mohla had earlier made Sharafat (1970) and Raja Jani (1972) with Dharmendra.) Every now and then, Dharmendra would beam at us with twinkling eyes.

When the stock-taking ended, he got up and walked across the room to us. I was introduced. He embraced me and said: “Mere putt da naa vi Ajay hai” (Sunny’s real name). We spoke for a while, and then he excused himself and went to another section, where his brother Ajit Singh Deol (actor, producer, and father of Abhay Deol) was holding fort with a group of NRI ladies waiting for Dharmendra. The ladies gushed endlessly, while an indulgent Dharmendra sat with them – attentive, smiling, and patiently answering every question.

A little later he returned, and my friend told him I was very fond of music. He asked which songs of his I liked. I told him that like him, I too loved Rafi – and that Rafi had sung the lion’s share of his songs. Dharmendra agreed and said Rafi’s last song was picturised on him (Aas Paas, 1981). I told him he was probably the actor with the maximum number of playback singers – 28, including P.B. Srinivas in Main Bhi Ladki Hoon (1964) and Kabban Mirza in Razia Sultan (1983). He seemed unsure and asked me to re-check; he thought Dev Anand held the record.

He looked surprised when I told him that despite Laxmikant–Pyarelal doing a staggering number of films with him (over 60), my top five songs of his were with other music directors: Ek Haseen Shaam Ko (Madan Mohan, Dulhan Ek Raat Ki, 1967); Mujhe Dard-e-Dil Ka Pata Na Tha (Chitragupt, Aakashdeep, 1965); Aap Ke Haseen Rukh (O.P. Nayyar, Baharen Phir Bhi Aayengi, 1966); Jaane Kya Dhoondti Rehti Hain (Khayyam, Shola Aur Shabnam, 1961); and Ya Dil Ki Suno (Hemant Kumar, Anupama, 1966) — a non-Rafi song. Dharmendra agreed the songs were fabulous, but noted they were not commercial ones. Surely, he said, there must be songs from the Laxmikant–Pyarelal stable that I liked. Mere Humdum Mere Dost (1968) had great songs, I agreed – especially Na Ja Kahin Ab Na Ja and Chhalkaye Jaam — but they were not in my top five.

He then asked, “Which films of mine do you like?” I told him I loved many, especially the ones from the 1960s. His role as a principled engineer confronting a corrupt system in Satyakam was truly inspiring, and the film rightly won the National Award. I said that although I enjoyed most of his films, his nuanced and sensitive portrayals in the black-and-white cinema of the 60s were my favourite phase.

Seeing my interest in music, Dharmendra asked my friend to show me Sunny Super Sound Studio nearby – a world-class facility with music recording, dubbing studios, and editing suites.

Later, we returned to Dharmendra’s house for lunch – urad dal (his favourite), gobi-aloo, and tandoori roti soaked in white butter. Delicious as hell. The lunch was served on the first-floor balcony overlooking Yash Chopra’s lawn in the adjacent bungalow. I asked Dharmendra whether the rumours of a falling-out between him and Yash Chopra over his role in Aadmi Aur Insaan (1969) were true. Dharmendra smiled and said, “Why rake up the past? You see his lawn? Yash broke the boundary wall when my daughter Vijeta got married, so that the invitees could be accommodated.” I asked him about his turning down the role of the elder brother in Waqt (1965). He laughed and said his loss was Raaj Kumar’s gain.

We took leave. Dharmendra bid us goodbye warmly and asked me to remain in touch.

I would meet him over the years at film and social functions, Income Tax events, and weddings.

Eight years later, I would stand in Yash Chopra’s lawn, look at Dharmendra’s bungalow, and remember that glorious Sunday filled with such warmth and care.

I belong to a musical group of amateur singers that regularly organises themed music programmes on Zoom. When we did a tribute to Dharmendra four years ago, he sent a video message to me and the group, lauding our hobby and wishing us the best. Who does that?

Dharmendra was like that. It is shocking that his trophy cabinet did not overflow with awards. But in the court of public opinion, he was a winner.

A teacher’s son from the hinterlands of Punjab who dreamt of doing what Dilip Kumar, Dev Anand, and Raj Kapoor did on screen – and hoped to own a flat and a Fiat as a consequence – Dharmendra emerged as one of the most loved icons of Hindi cinema.

Dharmendra represented dabangpan, seedhapan, sanskar, alhadpan, masti, and befiqri.

During his early years, the film industry’s leading publication Screen wrote:

“Newcomer Dharmendra contributes a tolerably good piece of work, although in the romantic sequences as well as in the tense moments, he is not quite at home. With better guidance, he should be able to do well.”

After more than 300 films under his belt, this now appears to be the understatement of the century.

Dharmendra, who also dabbled in poetry, wrote:

“Chahat hi boyi hai jo ab kat rahi hai

Shohrat chali jaati hai, chahat nahin.”Fame is ephemeral, but love is forever. Dharmendra is forever.

Rest in peace, the nation’s beloved Yamla, Pagla, Deewana. For 65 years, you kept us enthralled. The Neela Aakash is your abode now – and you will continue to entertain its denizens too.

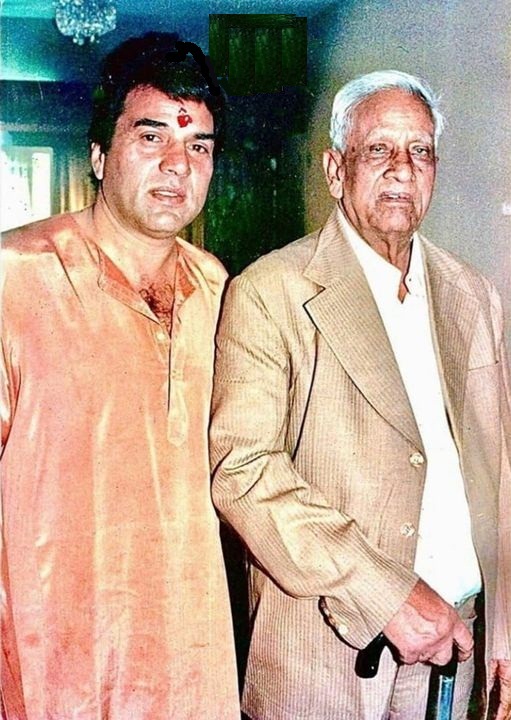

(Cover Photo: The President, Smt. Pratibha Devisingh Patil presenting the Padma Bhushan Award to Shri Dharmendra Deol, at an Investiture Ceremony-II, at Rashtrapati Bhavan, in New Delhi on April 04, 2012.jpg. PIB)

ajay mankotiaCinemaDharmendraHeroHindi filmsIndiaIndian CinemaSuperstarTribute