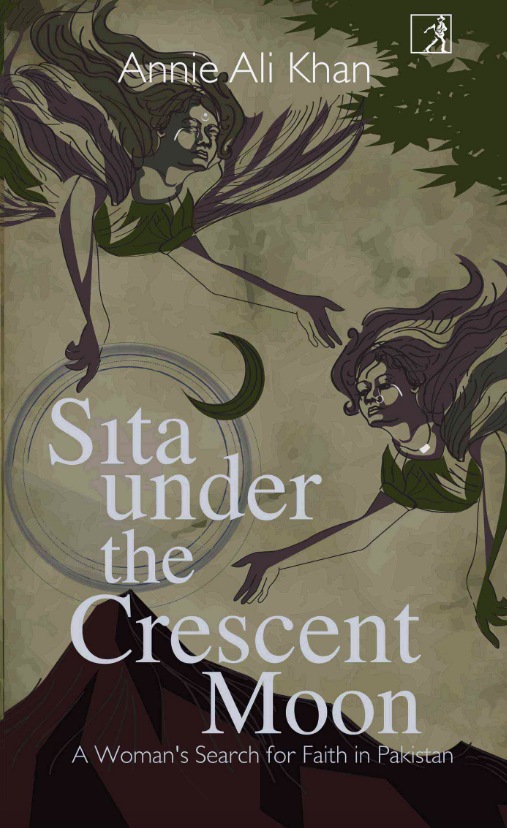

Sita under the Crescent Moon: A Woman’s Search for Faith in Pakistan

Annie Ali Khan

Simon and Schuster India, 2019

Pg 312

Price Rs 599

Annie Ali Khan died young, too young. She was born in 1980 in Karachi. She died on July 21 in 2018 in Karachi, in an unfortunate accident. Her original name was Qurutulain Ali Khan, and she should not have died so young. It’s a tragedy. Her notebooks remain incomplete, so does her quest.

A journalist, model, writer, photographer, and solitary traveler, with a master’s degree from Columbia University, she had miles to go before she found repose or sleep. Hitch-hiking, trekking, riding on trucks and broken-down buses and jeeps, sleeping in open-to-sky courtyards, dusty and unknown small towns, in desperately poor houses, in fiercely male territories, inside shrines and temples, next to the dance of the dhamals, walking miles without food and water, documenting, listening, reading and rewriting, absorbing and thinking, participating and becoming and being – why and for what was she going through these incredible revelations and hardships? What was she searching for?

She seems to be looking for the incredible synthesis of multiple spiritual/syncretic and oral/folk/mythical traditions in the back-of-the-beyond interiors of rugged Pakistan, with women wonderers as her protagonists and companions, unafraid of civilised or fundamentalist terror, or male machismo, never succumbing to surrender or fear or prejudice, celebrating desire and longing and the thirst for salvation on earth, and stories, many more stories, unwritten stories, hidden stories, camouflaged stories, stories of love and sex and compassion, carved on the sand and soil of her long, thirsty journeys.

She has been stretching herself out, always an observer and detached, and yet totally involved and a participant, a friend, a beloved, a sister, a companion and a journeywoman, travelling into and from the far corners of Sindh and Balochistan, across undiscovered and rugged landscapes, looking for the threads of unity which unites the insanity of humanity, the sanity of humanity, the compassion and brutality of humanity, the ecstasy and catharsis of liberation, the mixing of rituals, beliefs, faiths and narratives, the unfolding of the hidden kaleidoscope, the oral traditions, the invisible shrine, the shrine way beyond in the tiring, thirsty hills, or the desert. The image on the wall, the goddess in her enclosure, the dance of the dervish, the song of the road, the love lost forever, the sleep which she found so young and which took her away from us, and her loved ones, forever.

It was truth I sought as my life passage into Balochistan, armed with a notebook, camera and an audio recorder, with the vague outline of a story in my head. I was accompanying a family of ‘yatris’ on a pilgrimage to the temple, entering the highly patrolled and policed borders of the province with them.

That is why this book resurrects her unfinished journeys, like an unfinished sentence, an incomplete poem, a half-empty canvas, her impassioned notes and passionate writing, her sublime, mystical, mythical, realistic book of realism, like a chronicle of a story foretold. Truly, she could have, she should have, lived and walked for many more miles, before she could sleep her final repose. Her journeys are still incomplete and her departure too sudden, and shocking, steeped in sadness.

Her first journey is into and through the desert, miles, and miles of the expanse of desert and rough landscapes, to the shrine of Hinglaj, at once Hindu but neither Hindu nor Muslim nor tribal nor Sufi, outside the system of organised or disorganised religion, celebrating the incredible brilliance and beauty of the magnificent goddess, in eternal sleep and silence, restful, in repose. Older generations of Bengalis know about Hinglaj, now in Pakistan, because of the famous song sung by Hemant Kumar with legendary film actor Uttam Kumar in the lead, thirsty and tired, walking in this eternal journey to seek salvation and wash away all sins of humanity, including those committed by others: Koto dur, aar koto dur, bolo Ma…( How far, how far, tell us mother…).

The song is part of Bengali cinema’s folklore, sung under the moonlight in childhood courtyards and remembered for its archival long and difficult journey. The famous film was ‘Moritirtho Hinglaj’ made by Bikash Roy in1959, starring Sabitri Chatterji, Pahari Sanyal and Anil Chatterjee, all great actors of their times, along with, of course, great Uttam Kumar.

Writes Annie: “It was truth I sought as my life passage into Balochistan, armed with a notebook, camera and an audio recorder, with the vague outline of a story in my head. I was accompanying a family of ‘yatris’ on a pilgrimage to the temple, entering the highly patrolled and policed borders of the province with them. It was also the last night of Navratri, the festival celebrating the victory in battle of the goddess Durga over a demon buffalo to restore dharma, the order of the cosmos. Sati’s suffering and sacrifice and the joy of her victory were remembered like Moharram, like mohabbat; love in the heart, eternal and ever-flowing, like the suffering was life on earth…

“Sati was a woman celebrated as a goddess after she was immolated. Her sacrifice, like the sacrifice of Karbala, was a reminder: nothing came without a price in this world. Like the shaheed lays down his life in struggle, the sati burned for a greater truth. Where the word ‘shaheed’ in Arabic is one who proclaims or one who witnesses the truth, the world ‘sati’ in Sanskrit means ‘real, true, good or virtuous’; Sati, the woman, burned on her husband’s funeral pyre….

Meeting Durga at Hinglaj reminded me of the sacrifices life demands at every step. I began to follow the satiyan, the seven sacred sisters, travelling, all through Sindh and Balochistan. I decided to make a pilgrimage for the seven women worshipped after being set on fire or swallowed alive by the earth.

“Sati was also alive—the Hinglaj Mata I met in Balochistan.”

The legend locally popular for centuries is that the great mother saint Nani Pir taught a lesson to an evil king, Hinglaj, notorious for raping the women of his own kingdom. Durga apparently roamed in his gardens in the form a beautiful woman. The king chased her into the wilderness where she turned into a terrifying deity. The king realised his mistake and sought forgiveness. He promised to serve her. Durga forgave him and became a statue of stone. Till this day, across religion, caste, identity and politics, beyond history and geography, people reach out to her in this difficult terrain to worship her and celebrate the idea of justice and forgiveness and the power of nobility and women.

This book is a notebook and a diary in magically lyrical prose of Annie’s travels with women devotees, “on pilgrimages to retrace the way they worship the goddess”. What is their relationship with spirituality, with female spirituality, with shrines, temples and pirs, renunciation, exile, desire, longing, fulfillment and camaraderie? How do they worship stones, statues and shrines and dance like dervishes in a country which seems so overtly, strictly and rigidly Islamic in the contemporary times? What is their relationship with Sati in Pakistan in these times and days of fundamentalism, violence against women, bloody campaigns against blasphemy and total irrationality, often marked by genocide and barbarism, and the mass murder of innocent worshippers in Dargahs, or children in school?

“Meeting Durga at Hinglaj reminded me of the sacrifices life demands at every step,” writes Annie. “I began to follow the satiyan, the seven sacred sisters, travelling, all through Sindh and Balochistan. The search for the elusive sati became a quest to learn more about the women burned or buried and then worshipped. I decided to make a pilgrimage for the seven women worshipped after being set on fire or swallowed alive by the earth.”

Durga has twin faces, with a serene expression. Perhaps, she has many faces and identities. In contrast to the Durga across Bengal and India, who arrives for a short journey early winter with the magical recitation of the early morning ‘Mahalaya’, and goes back with her bisarjan in the waters, leaving her worshippers in great sadness at her inevitable departure, she lies here, in sleep, in “perfect repose”. She lies on the floor of the cave, after drinking two bowls of milk offered by Shah Abdul Latif Bhitai, the poet-saint.

“The milk bowls were said to have been left there as offerings by the pilgrims. ‘Nani Maa,’ Latif said to Durga, calling her great mother or maternal grandmother. ‘Why don’t you drink the milk? Why are you sleeping?’ Durga is said to have reached over and drunk the milk from each bowl and then reclined and lay on the floor of the cave, as she is seen there today, perfectly in repose.”

Sati was a woman celebrated as a goddess after she was immolated. Her sacrifice, like the sacrifice of Karbala, was a reminder: nothing came without a price in this world. Like the shaheed lays down his life in struggle, the sati burned for a greater truth.

She opens an opening in the cave for Latif, into the dense darkness, so that he can reach home sooner than the long 200 miles of journey on foot. Latif becomes her worshipper. Tribals, Muslims, Hindus, women, mothers — they tie colourful cloth to the legend of Durga. They worship the reclining, solitary goddess, in repose and retreat. She will fulfill your wishes. She has fulfilled all wishes.

Annie Ali Khan dedicated this beautiful book of her spiritual journey with women comrades to great Urdu writer, Qurratulain Hyder, author of the celebrated epic: Aag ka Dariya – the River of Sorrow.