Hindi film music is replete with What-Ifs, Maybes and Might-Have-Beens.

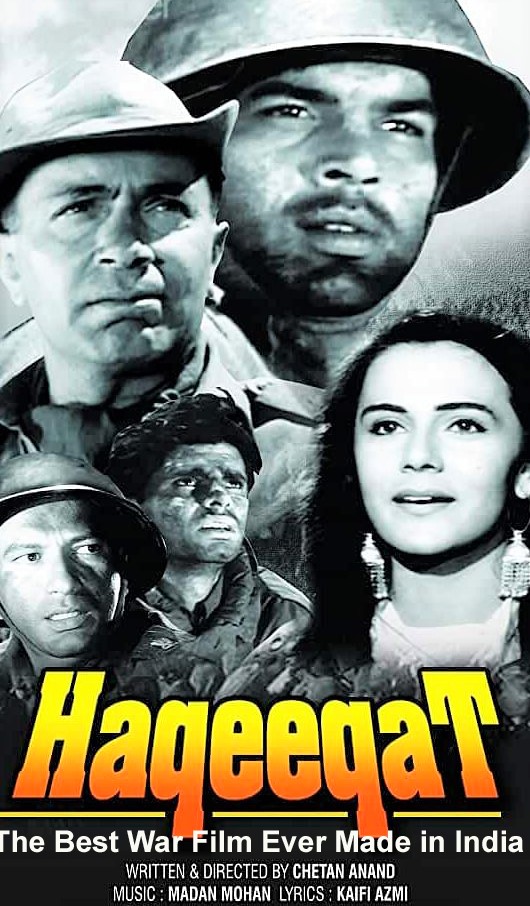

What if Madan Mohan had continued to serve in the Army? He had studied in Colonel Brown’s Military High School, Dehradun, completed one year military training in 1943, and joined the Army during the Second World War as a Second Lieutenant. But it was not meant to be. He resigned after the War to pursue his love for music. The Army’s loss was Hindi film music’s gain – an immeasurable gain. The sensitivity and the fine sensibilities that marked his music was a far cry from the gore and violence of the battlefield. Madan returned to the war zone, albeit in reel life, in Haqeeqat (1964) – with stunning music including the best patriotic song ever composed (though not widely acknowledged) in ‘ Kar Chale Hum Fida’; and Hindustan ki Kasam (1973).

What if Madan has found success as a singer, and not gravitated towards composing. In 1947, he had recorded two ghazals, and in 1948, two more. In the same year, he sang a film duet with Lata Mangeshkar under the baton of Ghulam Haider in ‘Shaheed’. There could not have been a better launchpad! But it was not meant to be and Madan was destined to be behind the microphone, not in front. And that allowed the music lovers to be held in thrall by the sheer magic of his compositions.

What if Madan had succeeded as an actor? He had a striking personality, was fond of body building, had a robust physique. He wanted to try his luck as an actor. The fact that he was the son of Rai Bahadur Chunilal Kohli, co-founder of Filmistan Studios, may have had a role to play. But again, fate had other plans. His first film as a hero – Parda – got shelved after completing almost eight to nine reels of shooting and his only film foray was restricted to brief screen appearances in Shaheed (1948), Ansoo (1953) and Munimji (1954). And that allowed the yet- to- be- mined treasure trove to be brought to the surface, to the utter bliss of the discerning listeners.

What if Lata Mangeshkar had continued to have a misunderstanding with him, arising out of the handiwork of his ill-wishers (rich playboy), and not patched up with him? She had refused to sing for his first film Aankhen (1950) for this reason? When the reality dawned, Lata apologized to him. Just as well. Else, Hindi film music’s once -in -an -era collaboration would not have seen the light of day. Interestingly, the first song that Madan sang, a duet with Lata – “Pinjare mein bulbul bole, Mera nanha sa dil dole” (Shaheed) was picturized on a brother- sister pair. Who would have known that the song would prophesize the Madan-Lata relationship with Lata becoming the rakhi sister of her Madan bhaiya?

We are glad that fortune behaved in the manner it did!

Madan and Lata were made for each other. Without Lata’s songs, Madan’s true genius cannot be gauged (even though he composed some outstanding songs for other singers). Similarly, without Madan, Lata’s oeuvre of musical gems would stand substantially diminished. Madan reserved the best tunes for her. Not that it didn’t rankle other singers. Asha Bhosle (who rendered the spectacular ‘Shoko Nazar Ki Bijliyan’ (Woh Kaun Thi ,1964) and the frothy ‘Jhumka Gira Re’ (Mera Sayaa,1966) confronted Madan about it. Undeterred, Madan replied that Lata would always be his first choice.

But why Lata? The answer lay in Madan’s compositional style. The words had to be sung in a manner to bring forth their beauty, their hidden meaning, their real intent. That required an emotional plunge into the deep waters of the music and the lyrics, to bring to the surface the pearls scattered on the sea floor. Madan was of the firm opinion that only Lata was capable of the deep dive.

Tunes, challenging ones, without sacrificing the melody, were crafted for Lata. She cleared them with full marks, with an appreciative nod of the maestro who never once doubted her ability to do so. What we got were songs that will remain eternal.

In the song ‘Chhaayee Barkha Bahaar’ (Chiraag, 1969), Lata spreads out the word ‘Chhaayee’ to bring out its exact meaning. Consider the three iconic unforgettable songs of Woh Kaun Thi (1964). Hear the way Lata renders ‘Phir’ in “Phir yeh haseen raat ho na ho” (Lag Ja Gale); ‘Kyoon’ in “Aap kyoon roye”; ‘Rimjhim rimjhim’ in ‘Naina Barse Rimjhim Rimjhim’ – each in a unique way to elicit the import of the word and the emotion underlying it.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TFr6G5zveS8

Madan was of the belief that Lata’s voice was best suited for intense emotional songs. The loneliness in her persona lead to the intense emotions in her singing. The nuances in her songs were rendered with minute details and fine restraint.

Such a made-in-heaven collaboration could not have been possible without a personal chemistry between the two. Such was the respect and affection Lata had for Madan that, after his demise, his children were married by her – her name even appearing on the wedding card.

Not that other singers didn’t sing outstanding songs of his – ‘Phir Wohi Shaam’ by Talat Mehmood ( Jahan Ara, 1964); ‘Bhuli Hui Yaadon’ by Mukesh ( Sanjog, 1961) ; ‘Har Taraf Ab Yahi Afsaane Hain’ by Manna De ( Hindustan Ki Kasam, 1973);’Simtee Si Sharmayee Si’ by Kishore Kumar ( Parwana , 1971) ; ‘Tum Jo Mil Gaye Ho’ by Mohammad Rafi ( Hanste Zakhm, 1973 ) ; ‘Aye Dil Mujhe Bataa De’ by Geeta Dutt ( Bhai- Bhai, 1956) ; ‘Shokh Nazar Ki Bijliyan’ by Asha Bhosle ( Woh Kaun Thi, 1964) , and many others. But Lata would always remain Madan’s priority number one.

Madan remained a man of the classes. His compositions, encompassing pathos, nostalgia, romance, registered in your mind, then percolated to your heart. His tunes were an acquired taste. That’s why they have no shelf life. Even his peppy, fluffy numbers mostly remained beyond the reach of the masses. Masses prefer casual, simple tunes – which can be sung under the shower – but they did not generally find a place in Madan’s compositional style. His songs required intellect to appreciate the intricacies of the poetry and the melody. That was his limitation. But a self-imposed one.

That’s why he was not a commercial success. If the man on the street can’t hum your song, you will remain confined to the drawing room. Your bank balance will forever remain modest. To his credit, Madan never compromised, and stuck to his core competency.

In his 25-year long career, out of his 95 films, only a handful became box office successes – Bhai- Bhai (1956), Woh Kaun Thi (1964), Mera Saaya (1966), Heer Raanjha (1970), Laila Majnu (1976). Films like Jahan Ara (1964) ran for only 4 days (No fault of Madan though – the film had superlative music, but the average listener probably did not agree).

Madan, while sticking to his style throughout his career, intelligently adapted to changing trends by changes in his tunes and orchestration, in a subtle way. So, whether it was Madan Mohan 2.0 or 3.0, it was always Madan Mohan! For example, hear the orchestration in the song ‘Tum Jo Mil Gaye Ho’ (Hanste Zakhm, 1973) – in its modern approach, it excels in creativity and impact. Like a hurricane, it begins like a gentle breeze, gradually gathers momentum, followed by a short lull, then moves into full throttle. The melody and orchestral passages reflect the changing mood of the song – the plea of the lover, its acceptance, followed by the fever-pitched joyous celebration. A genius was at work, incorporating modern techniques to a time -tested compositional style.

Madan’s proclivity towards the ‘ghazal ‘genre manifested itself under the influence of his Lucknow days in 1946 where he worked as a Program Assistant in All India Radio, where he interacted with Begum Akhtar, Talat Mehmood and Barkat Ali.

Lata has stated that the way Madan could compose ghazals, no one else could. He was in a different class altogether. Composing a captivating melody with all the necessary ornamentations to highlight the ghazal’s soul, was his forte. Each ghazal is a treasure and beyond measure.

Consider some of them – ‘Hum Pyaar Mein Jalne Walon Ko’ (Jailor, 1958); ‘Woh Chupp Rahein Toh Mere Dil Ke Daag Jalte Hain’ (Jahan Ara, 1964); ‘Agar Mujhse Mohabbat Hai’ (Aap Ki Parchhaiyan, 1964); ‘Yun Hasraton Ke Daag’, ‘Unko Yeh Shikayat Hai’ and ‘Jaana Tha Humse Door’ (all three from Adalat, 1958).

His peers also had high regard for him. Naushad once remarked that Madan’s two ghazals from Anpadh (1962) – ‘Hain Isi Mein Pyaar Ki Abroo’ and ‘Aap Ki Nazaron Nein Samjha’ were equal to all the songs he had composed in his life. A huge, unprecedented compliment from one maestro to another.

It was thus natural for Madan to be crowned, by listeners and peers, the Emperor of Ghazals. But this anointment also became his limitation. He got slotted, and could not escape from the pigeon-hole.

Not that Madan Mohan did only ghazals. His other works with Lata are equally noteworthy – ‘Doli Chadhate Hee Heer Nein Bain Kiye’ ( Heer Ranjha, 1970) ; ‘Main Toh Tum Sang Nain Milake’ ( Man-Mauji, 1962) ; ‘Woh Bhuli Daastaan’ ( Sanjog, 1961) ; ‘Meri Aankhon Se Koi Neend Liye Jaata Hai’( Pooja Ke Phool, 1964); ‘Jeeya Le Gayo Jee Mora Saawariya’ ( Anpadh, 1962); ‘Ja Re Badara Bairee Jaa’ ( Bahana, 1960) ; ‘ Meri Veena Tum Bin Roye’ ( Dekh Kabira Roya, 1957) ; ‘Do Dil Toote Do Dil Haare’ ( Heer Ranjha,1970) ; ‘Bairan Neend Na Aaye’( Chacha Zindabad, 1959) ; ‘Nainon Men Badara Chhaye’ ( Mera Saaya, 1966) and several others underlying Madan Mohan’s genius to craft a tune for any mood or situation. As the songs with Lata would reveal, he generally remained a serious composer for her.

Some songs of Madan have an interesting story to them.

While recording ‘Aaj Sochaa Toh Aansoo Bhar Aaye’ (Hanste Zakhm, 1973), Lata was so moved that she broke down twice during her rendition. Eventually, Madan could only record the music track that day, Lata dubbing the next day.

The most surprising part was that Madan Mohan was not formally trained in music, yet he explored the vast variety of raags in his tunes, much to the admiration of the connoisseurs of Indian classical music. Reportedly, Bade Ghulam Ali was once singing a thumri in a mehfil when the song ‘Kadar Jaane Na’ (Bhai-Bhai, 1956) wafted in from a radio close by. He immediately put his harp down and commented that this was perfect singing and that he won’t sing any further.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=T76k9oCbLUg

An amusing incident took place while filming ‘Naina Barse’ (Woh Kaun Thi, 1964). Lata was not available so Madan recorded the song in his voice. It was a strange sight for the bystanders to see a petite Sadha lip-synching to a male voice.

Yet for all his mammoth abilities, he didn’t win the Filmfare Award – the gold standard of popular appeal. The critical appeal came in the form of Sur Singar Samsad awards for ‘Maine Rang Li Aaj Chunariya’ (Dulhan Ek Raat Ki, 1967), and ‘Nainon Mein Badara Chhaye’ (Mera Saaya, 1966); and the National Award for Dastak (1970) mainly due to Lata’s classical, and classy, trio – ‘Baiyan Na Dharo’, ‘Maaee Ree Main Kaase Kahoon’, and ‘Hum Hain Mate -E-Koocha’.

Madan also worked in All India Radio, Delhi in 1947 where my maternal uncle Satish Bhatia also worked (he retired as Chief Producer, Light Music). They became close friends and Madan would always meet him whenever he came to Delhi. In one such meeting in 1962 – a dinner at my uncle’s place- he met Bhupinder, who was a guitarist under my uncle in AIR, Delhi. Madan requested him to sing, and was impressed enough to invite him to Bombay to record ‘Hoke Majboor’ (Haqeeqat, 1964) along with Rafi, Talat and Manna De. In 1975, Bhupinder would sing ‘Dil Dhundta Hai’ (Mausam, 1975) under his baton.

By 1970s the musical tastes were changing. Madan was deeply hurt by the commercialization of music. He hit the bottle which would eventually lead to his death on July 14, 1975. The composer who though that he wasn’t adequately appreciated, bizarrely found fame and recognition for his mediocre score in Laila Majnu in 1976. There was more to come. A treasure trove of hundreds of his unutilized tunes were discovered by his son. Some of these were released. A special mention needs to be made of the song ‘Tere Baghair’ – an outstanding Rafi rendition. Yash Chopra utilized some unused tunes in Veer- Zaara (2004). Lata naturally lent her voice to the songs, arranged in a modern orchestration style by Madan’s son Sanjeev Kohli which appealed, not only to Madan’s fan base, but a new generation of listeners too. The album became the highest selling album of that year.

Today is Madan’s birth anniversary. He was born on June 25, 1924 at Baghdad in Iraq. Madan may have left the world at the age of 51 (no age to die), but Madan the Composer can never die. He never blew his trumpet; he didn’t have to. Very early in his career, Madan was aware of the timelessness of his legacy that he would leave behind when Lata echoed his self-belief in the song from Baghi (1953) – “Hamare baad ab mehfil mein afsaane bayaan honge/ Baharein humko dhoondegi, na jaane hum kahaan honge”.