A rich archive of intelligence reports suggests that the October Revolution of 1917 had left the British in India paranoid and jittery, prompting them to spy on several revolutionaries and activists in order to muzzle the nascent red wave before it could find an anchor in India

On October 24, 1917, Lord Sydenham rose to speak in the House of Lords, and said, “No graver warning of what revolution may mean has ever been given, and the conditions in India very closely resemble those in Russia, except that the Indian people are far less homogeneous and there are far more racial and religious antagonisms among them than anything which exists in Russia.” His speech, a part of the debate on whether the freedom of press and speech in India should be curbed, argued vehemently for the curtailment of such rights to Indians. His argument was straightforward: Indians are a people who are ignorant and readily willing to believe anything and may follow the path of extremism. In seeking examples from the world, he chose Russia.

The British were wary of the chain reaction that the October Revolution could unleash in India and its other colonies. As Lincoln Stiffens, a reputed American journalist, wrote, the Russians were the first to knock out the old system, “to remove privileges, to set out to abolish poverty, riches, graft, privilege, tyranny, and war.” The cause of much consternation to the British was that the cornerstone ideal that the revolution was built on, as vocalised by Vladimir Lenin and other revolutionaries, was the idea of ‘self-determination’ for all people. Lenin, much like Karl Marx, was vehemently opposed to the tyranny of imperialism. Once in power, the Lenin-led Bolshevik government led by example, dismantling the six-centuries-old Tsarist rule. They broke the Romanov empire by first liberating Poland, Finland and other nations. By January 1918, the new government in Russia was lending support to Persians, promising them support in their fight against both the British and the Turkish occupation.

If intelligence reports of the time are to be believed, the British were in a state of constant fear of a breakout similar to the Bolshevik revolution. All forms of unrest in the colonies post-1917 were linked to Russia. They carefully constructed a counter, collected intelligence and in many cases even infiltrated and subverted areas of brewing tension.

The British Indian government was meticulous about its paranoia. The constant fear of an armed insurrection against the empire had forced it to create a complex web of intelligence gatherers.

In India, newspapers such as Chitramaya Jagat, a Marathi daily, understood the gravity of the change sweeping Russia and through it the world. A month after the revolution began, articles appeared in the newspaper lauding the movement for self-determination as charted out by Lenin. The revolution gave the Indian nationalist movement new vigour and an ideal to follow. The Jagat and other newspapers attempted to simplify the movement for their readership. The ideas of a united worker and peasant front began to find greater and wider articulation in speeches and writings of the nationalist movement in India.

This shift in propaganda had the British worried. Sensing the possibility of an armed insurrection in the colonies, the news wires and papers of the empire began to create propaganda against the Bolsheviks, calling them an army of violent hooligans. On November 14, 1917, while the war raged in Europe, the Times of India carried a headline on page 7, ‘Russian Crisis: Doom of Leninism.’ The story questioned the narratives coming out of Russia “as they (were) all Leninist” in nature.

By July 1918, the Times of India was publishing articles with headlines such as ‘Bolshevik Terror’ which said that the revolution, that was widely supported, had assumed the dictatorial and autocratic character of the Tsars — a regime strongly opposed by all. The paper reminisced about the February revolution, calling it the real revolution, and the one led by Lenin and the Bolsheviks as something violent that eroded the idea of Russia.

Perhaps what attracted people to the Russians was not the promise of socialism, Communism or Bolshevism, but that of revolution and, as Leon Trotsky put it, the state of ‘permanent revolution’. Helped by the thrust of Soviet foreign policy to spread Communism to other parts of the world, the party began funding ‘nationalist’ activity in other countries. It provided money and weapons, education and assistance.

Perhaps what attracted people to the Russians was not the promise of socialism, Communism or Bolshevism, but that of revolution and, as Leon Trotsky put it, the state of ‘permanent revolution’. Helped by the thrust of Soviet foreign policy to spread Communism to other parts of the world, the party began funding ‘nationalist’ activity in other countries. It provided money and weapons, education and assistance.

By 1930, the Russian influence had significantly grown over the subcontinent. They had helped mould a newer leadership that was not averse to Communism or socialism to the extent that both Mahatma Gandhi and Jawaharlal Nehru interfaced with the rise of the Soviet movement differently. For Gandhi, it became something to distance himself from and build his own homegrown political movement, while for Nehru it was something he lived in awe of — an ideal breakdown of an old political system, fashioned by ideals. The future prime minister was not concerned with the practical implications of the everyday working of the State. In the United States, one notable example was the Ghadar Party which was founded by Punjabi Sikhs with the aim of securing India’s independence from British rule.

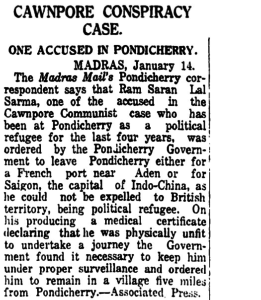

Since 1919, the intelligence services in India had been watching the rise of Communist thought in the country but it was only in 1924 that the Kanpur Conspiracy Case acted as a way to neuter the movement in India and exposed the Communist plot to the public. The verdict only served as a way of keeping closer tabs on activists such as Shaukat Usmani, M.N. Roy, Nalini Gupta and S.N. Dange, who as a result of this case were booked for conspiracy to deny the “King Sovereign the right to govern India” and accused of receiving money from the Soviets to build propaganda. Cecil Kaye was one of the main actors in this trial.

Cecil Kaye and David Petrie

The British Indian government was meticulous about its paranoia. The constant fear of an armed insurrection against the empire had forced it to create a complex web of intelligence gatherers. After the end of the Great War, the successive heads of the Intelligence Bureau in India left two rich accounts of the rise of Communism in India and Soviet propaganda in the aftermath of the revolution.

David Petrie (MI5)

Cecil Kaye, the head of the Intelligence Bureau between 1919 and 1924, was entrusted with collecting information on the growth of Bolshevism in India. After the Kanpur Conspiracy Case, Kaye felt compelled to pen down the threat of Communism in India. He wrote a book, published by the government of India, in which he detailed the keeping of close tabs on all the leaders, following their movements, speeches and meetings. He sent his detailed, often exaggerated notes back to the India Office. David Petrie carried forward the work done by Kaye and added a thick description of the labour movement, unions and their growing importance in the political machinations of the country.

There is an overlap in the work of Kaye and Petrie. The monograph written by Petrie is fascinating because of the last chapter ‘appreciation’, in which he has written his thoughts on the subject. He attempted to break down the progress, questions and objectives of the Communist movement in India. Both intelligence officers operated on the basis of what they called ‘The Thesis,’ which they pulled out from the writings of Manabendra Nath Roy’s Vanguard: the nationalist movements in colonial or semi-colonial societies will take the form of a revolutionary struggle which will later manifest itself in a world revolution. The tying of the anti-imperial agenda to the national movement was a masterstroke by V.N. Chattopadhyay and his international revolutionary front. It was he who convinced Lenin to give support to the Indian movement. In India, the movement was led by Roy, who became its most visible face.

Under constant surveillance, Roy’s letters were intercepted, his travels and associates shadowed and his life constantly jotted down by Kaye’s staff. Kaye devoted pages and pages to Roy, to the extent that he writes, “[Roy] has played such a prominent part in the Communist campaign against India, that it is worthwhile to give a brief account of his history.” It was through Roy and his publication, Vanguard, that the Soviets entered Indian political life. While their overall importance in India admittedly might be blown out of proportion, the role that Roy played cannot be discounted.

Under constant surveillance, Roy’s letters were intercepted, his travels and associates shadowed and his life constantly jotted down by Kaye’s staff. Kaye devoted pages and pages to Roy, to the extent that he writes, “[Roy] has played such a prominent part in the Communist campaign against India, that it is worthwhile to give a brief account of his history.” It was through Roy and his publication, Vanguard, that the Soviets entered Indian political life. While their overall importance in India admittedly might be blown out of proportion, the role that Roy played cannot be discounted.

Roy was a revolutionary, thinker-philosopher and activist. His credentials include founding both the Mexican Communist Party and the Communist Party of India, and later the Radical Democratic Party of India. As a young man, during the outbreak of the First World War, he joined the radical movement in Bengal which believed in an armed struggle. He left the country to find armaments and provisions to fight the British imperial government. In 1916, he found his way to Mexico where he became one of the founders of the Communist Party. He was also invited to the Second Communist International in 1920 where he met Lenin and decided to lead the Communist movement in India. Shortly after the Comintern, Roy and several others met in Tashkent and formed what is considered a precursor to the Communist Party of India.

the nationalist movements in colonial or semi-colonial societies will take the form of a revolutionary struggle which will later manifest itself in a world revolution

According to Kaye’s report, Roy had tried to bring arms and money into India through Afghanistan and continued to receive large amounts of gold roubles from Russia to help spread propaganda. The British regarded themselves as the bulwark against the scourge of Communism and to them Roy was an intermediary between India and the Soviets: a manifestation of the fear that the Third International would act as a counter to the imperial power of Great Britain. The British believed that the Russian efforts would begin with dispossessing them of India.

Roy became the obvious face of a Soviet-backed conspiracy. Along with other members, all part of the Kanpur Conspiracy — Nalini Gupta, Muzaffar Ahmed, Shaukat Usmani and S.N. Dange — they sought to help spread the word of Communism. Through his writings in Vanguard, Roy communicated not only with those predisposed to the ideology but also served as a mouthpiece of Moscow.

The aim of the British was to nip the Communist movement in the bud. After collecting enough information, identifying large amounts of money coming to Roy and others, the IB was able to create a case for sedition against the nascent Bolshevik movement. They were taken to court where Kaye testified against them — presenting letters, articles and money orders. Roy escaped, while the rest were given a minimum of four years in prison.

However, this was not the end of British woes with the ideology that was unleashed by the October Revolution. In the decade between 1917 and 1927, a trade union movement was engendered. Several trade unions came to become a major factor in the political process in India. The British in India during 1926–27 were confronted by hundreds of strikes in all sectors: railway workers, the anglo-American oil workers, mill workers.

Petrie commented in his book that all these unions were started or had members of the Communist Party. These unions had a press of their own and powerful means of propaganda. There were attempts by the Third International, an international communist organisation that advocated world communism, to co-opt this movement, but it steered clear. Petrie closes his comment by saying that while they possess the tools of communication, the labourers remain illiterate and the literature makes little impact on them.

BolsheviksCecil KayeColonialismDavid PetrieHistoryIndiaLord SydenhamRussian Revolution